If I asked you how a CD worked, how confident would you feel in explaining it to me? Let’s say from 1-10? A 7, 8 perhaps? Okay, go on then, explain it, but in so much detail that I completely understand. Not so confident now? We’re talking about a phenomenon called known unknowns and unknown unknowns.

Don’t worry, it sounds complicated and a bit confusing, but it really isn’t. It’s all about ignorance and how we perceive our knowledge to be of something.

I want to give you some more examples of known unknowns vs unknown unknowns before I explain this further.

You probably feel quite confident in your ability to answer the first four but pass on the last two. In fact, studies show that we are actually quite ignorant when it comes to everyday things.

We like to think we know more than we do, but we don’t. And this is where known unknowns and unknown unknowns come into play.

We are quite happy to admit we are not rocket scientists or that we couldn’t perform brain surgery, but the simple things in life? We like to think we know everything we need to know.

Known unknowns are the things we know we don’t know about, if that makes sense. Like space travel, brain surgery, how self-driving cars work. We know we need to research these topics to learn more about them. But the important thing is we also know that we’re not really expected to know about things as complicated as rocket science.

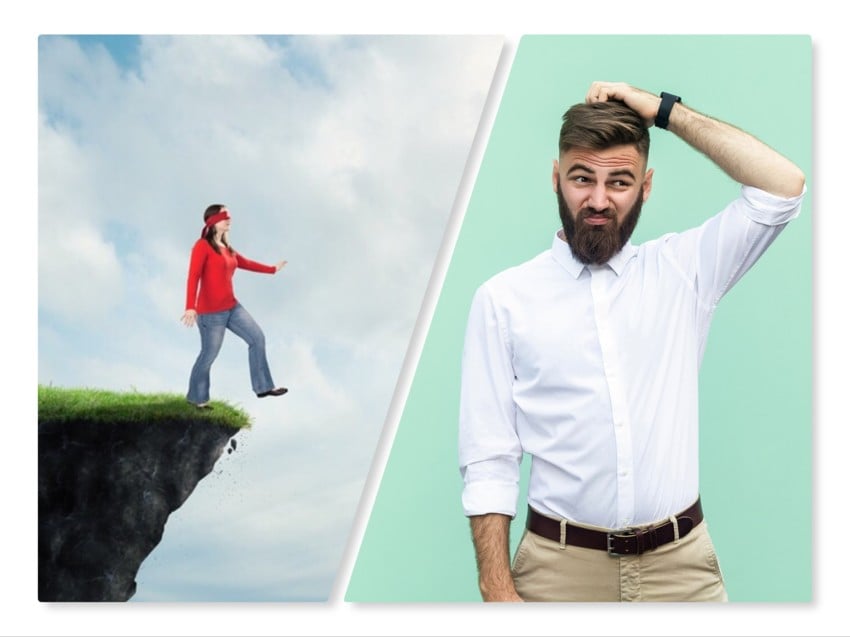

Now, unknown unknowns are the things we think we should know about, but we actually don’t. Like, how a bicycle works or what makes a toilet flush.

These are the simple, everyday things in life we take for granted and assume we know how they function. But we don’t. But we don’t know we don’t. The important thing with unknown unknowns is that we think we are expected to know about them.

It’s called the illusion of explanatory depth.

“Most people feel they understand the world with far greater detail, coherence, and depth than they really do.” Leonid Rozenblit and Frank Keil (2002)

Rozenblit and Keil conducted multi-phase studies to test the illusion of explanatory depth (IOED).

In the first phase, they asked participants to rate how well they understood the workings of objects such as sewing machines, mobile phones or bicycles.

In the second phase, they were asked to explain in a detailed report of how each object worked. They then re-rated their understanding of how each one worked. The results showed again and again that their confidence in understanding the workings of an object fell drastically from phase one to two.

In another study, Rebecca Lawson asked participants to draw a bicycle in her Science of Cycology report. Some of the results are featured below:

In fact, it doesn’t matter whether we are talking about the workings of objects or scientific theories or the stock market. IOED is this pervasive feeling we know more than we do.

The main reason for the ignorance of our own ignorance is that we don’t need to know how everyday things work. They just do. Generations that came before us invented them and they have been in our lives for decades.

We are used to seeing them wherever we go. They are part and parcel of the fabric of life. Thanks to others, we haven’t had to invent them; we just use them. So there’s no need for us to know the ins and outs of the workings of a toaster or a bicycle.

I liken it a little to spellcheck. Sure, we could learn every difficult word there is in the world by heart, but why bother? Our computers have spellcheck, so we don’t need to make the effort to learn. But we wouldn’t call ourselves stupid because of this.

It’s the same with gadgets, theories or mechanics.

Now, more than ever, thanks to search engines and sharing information, we can find out a lot more than our predecessors. We can look things up on Google, share content but more importantly, build on what our previous generations have already made.

And we don’t need to know how things work to be able to do this.

The other thing about our generation compared to previous ones is that by sharing information, we give ourselves the illusion of knowledge.

If I asked you why the planets are round, or what causes gravity, you wouldn’t throw your hands up in the air with despair. You’d look it up and tell me the answer.

It’s this instant access to knowledge that gives us all expert status when we are not experts. But the lines are blurred. And we certainly don’t consider ourselves to be stupid when we can research the answer.

But it’s not just this kind of instant access to information that gives us IOED, it’s the way we consume this knowledge.

We skim the top of news items, we click on salacious headlines for the juicy parts of a story, and we allow tweets to inform us of global political moves. We tap into viral videos, we listen to soundbites and agree with memes.

This is a superficial way of ingesting knowledge. We never really deep dive into a topic. As a result, we know a lot of stuff, but not in that much detail. In other words, we know a little bit about a lot.

When we believe we know more than we actually do, it can lead us to prejudice without us even knowing.

One study tackled how understanding people and IOED could help reduce political extremism. In 2013, Philip Fernbach et al asked participants to rate how well they understood a range of policies such as:

Participants were then asked to explain in detail how each one worked. Afterwards, they had to re-rate their knowledge on the subjects. As expected, their confidence fell after they were asked to fully describe the policies.

But here’s the interesting part, as their confidence fell, so did their extreme views on the policies. Those that either strongly opposed or supported the policies became more moderate in their views. And as their views became more moderate, so did their reluctance to fund these policies also reduce.

This study is an example of how IOED could be used to encourage a more moderate approach to political extremism.

I always use this example to show how people always think they are right, if for no other reason than it makes you think about the other side. Amaryllis Fox was a former undercover officer for the CIA and has met a lot of opposing factions in her time.

“If I’ve learned one lesson from my time with the CIA, it is this: Everybody believes they are the good guy,” CIA Officer Fox

We can’t possibly know everything and we can’t always be right. Understanding that we are all susceptible to IOED could lead to a more empathetic world for all of us.

References:

View Comments

Absolutely! A little knowledge is a dangerous thing. This is how politicians get the agendas they want passed into laws. How drugs are regulated into 'medicines' without testing the side effects thoroughly. And how planned parenthood has been used as a form of eugenics against minority races.

In truth much of what you think you know turns out, with very little investigation, to be propaganda; for instance: Columbus discovered America, the George Washington chopped down a cherry tree story and Abe Lincoln walked several miles to return a penny to a woman whom he mistakenly short changed.

Not only is ignorance the precursor to bias and prejudice, it makes you hopelessly dependent on the consumerism system. Understanding how things work is the absolute basis of consumer independence. Back when microwaves were quite expensive, I would find good quality clean ones by the curbside waiting for the trash. Most didnt work because it blew a $1.00 fuse or a wire was poorly soldered and separated. After fixing them I would give them to people who couldnt afford one. The same with vacuums, especially the bag- less type that had a foam filter that was never cleaned or replaced. Many times it is just a matter of reading the owners manual for trouble shooting problems but people cant even do that anymore.

I am a habitual reader and researcher. I read about any and all subjects from religion to quantum physics; from peer reviewed science to fringe science; organic oils vs synthetic oils, Intelligent Design to Evolution; Anthropology, Archaeology and even Forbidden archaeology. I am no expert but I can hold my own in any debate with just about anyone. Ive read extensively on child abuse, empaths, narcissism and psychopathy.

That has made me confident in who I am and why I am the person I have become. I have replaced many of my former beliefs with understanding now, and I work very hard at remaining open minded, always ready to listen to an 'intelligent' explanation from someone with different views than mine.

Everyone has a story to tell and everyone has the beliefs they have for a legitimate reason; someone or something had a major impact on them at some time in the past. I just ordered a book from Daniel Denner called, "From Bacteria to Bach and Back"; not because I liked what he was saying, in fact I disagreed with much of what he said in the video promoting his book; but because of the passion he has for what he wrote. And I admire people with passion and I hope I will learn something and get a little more understanding of the human condition.